Chapter 1 Prägnanz in visual perception

As humans, our visual abilities are amongst the most important tools we possess to enable immediate interaction with the world around us. Without visual perception, many everyday activities like preparing breakfast, navigating the streets, and reading, become much more exhausting or even impossible.

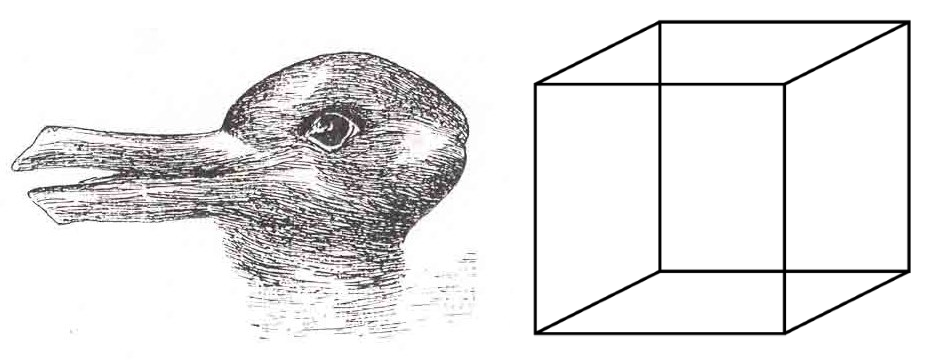

Although vision is sometimes presented as fully determined by the physical input it receives (i.e., light signals falling on the receptor cells in the retina), this is not the full story of how our perceptual experiences come about. An evident illustration is the existence of multistable figures like the duck-rabbit figure or the Necker cube (see Figure 1.1). Although the physical input is exactly the same, these figures are perceived differently across individuals, contexts, and time. Visual perception is an active construction process, not only for obviously multistable figures. Even in so called clear-cut displays inter- and intra-individual differences exist based on, e.g., perceptual skills, viewing mode, expertise, vigilance level, and temporal or spatial context. Koffka (1935) already acknowledged that things look as they do, not because things are what they are (veridicality), nor because of the proximal stimuli (i.e., the physical stimulations of the sensory receptors) are what they are, but “because of the field organization to which the proximal stimulus distribution gives rise” (p. 98). In other words, to understand why and how we visually perceive the world in the way we do, we need to study the laws of organization (Koffka, 1935).

Koffka (1935) presented the law of Prägnanz as the main principle to guide research on perceptual organization. This law states that psychological organization will always be as “good” as the prevailing conditions allow: we will always organize our visual input in the best way possible. However, what does it mean for a psychological organization to be “good” or “prägnant”, and what are the prevailing conditions to take into account? Notwithstanding the abundant reference to Prägnanz in many journal article introductions and discussion sections since its emergence, the concept has remained very vaguely defined. In addition, the original Gestalt psychological context in which Prägnanz originated got lost, and the interpretation of Prägnanz has changed together with the shifting theoretical context (i.e., increasing focus on information processing theories).

The overall aim of this project is to develop a more fine-grained understanding of Prägnanz (i.e., “goodness” of organization) and its added value for current theories and research on human visual perception. Thoroughly understanding what Prägnanz and the law of Prägnanz mean and can mean for current perception science requires

- thoroughly investigating the existing literature on Prägnanz, the factors on which it depends, and its implications; this includes studying original sources introducing and extending the concept as well as sources clarifying later interpretations, proposed measures, and critiques of the Prägnanz concept;

- conducting new empirical research to test hypotheses derived from refined insights enabled by this literature study; and

- comparing and potentially integrating the Prägnanz idea with current theoretical perspectives on visual perception (i.e., predictive processing theory, complex dynamical systems theory, Jan Koenderink’s theory of vision as an optimal user interface) as well as with current research.

The aspired outcome of this project is a further specification of the definition of “goodness” or Prägnanz, the conditions to which it is susceptible, its role in perceptual and higher-order processes (including discrimination, categorization, and aesthetic appreciation), and the ways in which Prägnanz can foster current perception science.

From studying the literature on Prägnanz (Chapter 2), it will become clear that to achieve the best organization possible, interacting tendencies are needed that are both antagonistic and complementary. To survive in the world, an organism needs both robustness and sensitivity to change (Chapter 3), hysteresis and adaptation (Chapter 4), order and complexity (Chapter 5), simplification and complication (Chapter 6). These concepts are antagonistic to some extent, but they are also complementing each other to optimize a balance. What entails the optimal combination of both will be flexibly adjusted to the individual, input, and context.