Chapter 2 Conceptual development

Status: literature review: manuscript in preparation; development of conceptual framework and integration with current theory and research: work in progress; general ideas presented orally (Van Geert & Wagemans, 2018c) and as conference posters (Van Geert & Wagemans, 2018b, 2018d, 2020)

Further development of the Prägnanz concept and assessing its merit for current perception science is an on-going task throughout the project. Getting access to the original sources on Prägnanz was not a trivial task and was only possible through some library visits across Europe as well as help from international acquaintances. An elaborate review paper on the historical development of Prägnanz and its later conceptions, as well as a shorter more general summary for a broader academic audience, focusing on the insights Prägnanz can bring for current theory and research, are in preparation. In the upcoming period, the main focus will be on comparing and potentially integrating the Prägnanz idea with current theoretical perspectives. Those include predictive processing theory, complex dynamical systems theory, and Jan Koenderink’s theory of vision as an optimal user interface. To facilitate this integration, I will extend my knowledge about the current theoretical frameworks by attending (a) a workshop on predictive processing and (b) a summer school on complexity science.1 In a later phase of the project, I will also evaluate and elaborate the Prägnanz framework in the light of the existing empirical literature and new empirical results deriving from the project.

Full review of the Prägnanz concept and its history is impossible in the context of this report, so I will only discuss the main points that are needed to be able to understand the further development of the project.

2.1 The meaning of Prägnanz

What does Prägnanz mean? Besides referring to a property of an overall organization or Gestalt, Prägnanz also refers to a tendency present in each organizing process. Some other Prägnanz-related concepts such as Prägnanzstufen and good Gestalt have connections to both meanings.

2.1.1 Prägnanz as a property of a Gestalt

As a property, Prägnanz concerns the simplicity of the Gestalt (i.e., the whole, overall organization). In contrast, it does not refer to the simplicity of the process of forming a Gestalt, nor to the simplicity of the individual elements forming the Gestalts. Wertheimer (1923) already indicated that it is not necessarily the simplest stimuli that produce the simplest perceptual groupings (Wertheimer, 2012, p. 307).

Although many assume Prägnanz to be related to the English word pregnancy (derived from the Latin word ‘praegnans’, meaning rich in potential content), Prägnanz actually derives from the Latin verb ‘premere’, which means sharply grasping, unambiguous, clear, or distinct (Arnheim, 1975). This meaning fits very well with Metzger’s (1941, p. 62) description of Prägnanz: for each essence, there is a structure in which the essence is most purely and compellingly realized, which we call ausgezeichnet or prägnant.

What does it entail for a Gestalt to be simple, pure, or compelling? Edwin Rausch (1966) distinguished seven major aspects of Prägnanz as a Gestalt property, of which the first one is a requirement: a Gestalt needs to show some degree of lawfulness or regularity rather than randomness to be called prägnant. In addition, a Gestalt is more prägnant: (a) when it is autonomous rather than derived; (b) when it is complete rather than disrupted; (c) when its structuring is simple rather than complicated; (d) when its elements are complex rather than simple; (e) when it is expressive rather than expressionless (in the sense that it expresses an essence more purely); (f) when it is meaningful rather than meaningless (in the sense that you have other knowledge about the Gestalt than only the formal-structural information).

2.1.2 Prägnanz as a tendency in each organizing process

When we use Prägnanz as a tendency present in each organizing process rather than as a property of a Gestalt, we speak of the Prägnanz law or the Prägnanz tendency. The original formulation comes from Wertheimer (Schumann, 1914), who described his success in ascertaining, under several Gestalt laws of a general nature, “ein Gesetz der Tendenz zum Zustandekommen einfacher Gestaltung” or a “Gesetz ‘zur Prägnanz der Gestalt’” (Schumann, 1914, p. 149). The Prägnanz law states that each organizing process will tend towards the most prägnant Gestalt possible under the prevailing conditions (Koffka, 1935, p. 110). This Prägnanz tendency is meant to apply to all forms of psychological organization (e.g., also those related to memory and thinking), not only those related to perception (Metzger, 1941; Wertheimer, 1945, 1959).

The formulation of the Prägnanz law requires further clarification of two elements: (a) how the Prägnanz tendency can be realized; and (b) which prevailing conditions need to be taken into account.

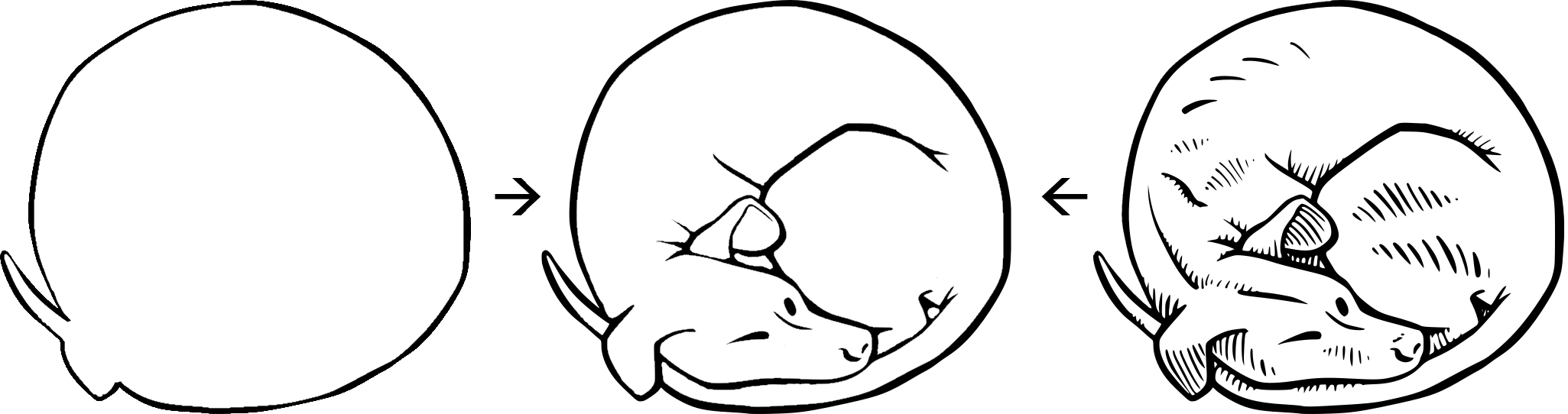

First, how can the tendency towards prägnant Gestalts be realized? Although typically only simplification of Gestalts is discussed (i.e., removing distracting, unessential detail, levelling, the simplicity of uniformity), Prägnanz can also be improved by emphasizing characteristic features of a Gestalt (i.e., sharpening, complication, the simplicity of perfect articulation; see Figure 2.1; Koffka, 1935; Arnheim, 1986; Hubbell, 1940). Simplification and complication do not have to be perceived as alternatives; both can be concurrently present to different extents as antagonistic and complementary tendencies in every perceptual event (Arnheim, 1986, p. 822).

Figure 2.1: Simplification and complication can both contribute to the Prägnanz of a Gestalt. The Prägnanz of the leftmost image can be increased by complication (i.e., adding or intensifying characteristic dog features), the rightmost one by simplification (i.e., removing unnecessary details). Image adapted from “Perro” by Juan Manuel Barreneche licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Second, what do the prevailing conditions entail? These conditions are dependent on the organism in which the organizational process takes place (Koffka, 1935). In the context of human perceptual organization, Koffka (1935) distinguished external conditions (created within the receptor organs by proximal stimuli) from internal conditions (related to the human nervous system), and within the internal conditions, more permanent ones (related to the structure of the nervous system, influenced by both inheritance and previous experience) from more temporary ones (related to e.g., vigilance, fatigue, needs, attitudes, interests, attentions). How strong the Prägnanz tendency will be, will depend on both internal and external conditions to which the organism is susceptible: The internal forces of organization will draw the percept towards the most prägnant shape possible and will thus strengthen the Prägnanz tendency; the external forces of organization represent the forces of the proximal stimulation on the percept and will constrain the trend towards Prägnanz of Gestalts (Koffka, 1935, pp. 138–139).

In summary, the Prägnanz law entails a tendency towards attaining the simplest overall organization, which can happen by removing unnecessary details as well as by intensifying characteristic features of the Gestalt (Arnheim, 1986; Hubbell, 1940). This tendency is influenced by both external and internal conditions, including the organism’s energy level, its current context, and its perceptual history.

2.1.3 Prägnant steps

One function of prägnant Gestalts is that they can serve as reference points for comparison. If one varies a component in systematic, physically equidistant steps, the resulting psychological impressions will not be equidistant; the progression will be discontinuous as particular prägnant steps (i.e., Prägnanzstufen) occur, that each have their own range (of influence). Steps in-between those prägnant steps are “not unequivocal to the same degree, not quite as prägnant, ‘less definite’ in their character, less pronounced, and often more easily seen in terms of one grouping or the other” (Wertheimer, 1923, 2012, p. 317), and will most easily be seen in the pattern of one of these prägnant steps (Prägnanzstufen), and appear as a somewhat “poorer” version of it. In case of unfavorable viewing conditions, the Prägnanz tendency will be more extreme, and assimilation to the prägnant Gestalt may occur.

The Prägnanz law implies a clear asymmetry: less prägnant Gestalts tend towards more prägnant ones, not the other way around. This has implications for perceptual similarity as well: “the bad Gestalt looks similar to the outstanding one, but not the other way round.” (Metzger, 1941, p. 63). Prägnant steps will thus be very robust, in the sense that (a) they will serve as a reference point for a whole range of percepts; and (b) it is hard to change the subjective interpretation of a prägnant Gestalt.

On the other hand, prägnant Gestalts are also said to be very sensitive to change: if one changes the Gestalt slightly away from the prägnant Gestalt, this will be perceptually noticed sooner than equally sized deviations from a less prägnant Gestalt.

Three types of less prägnant forms can be distinguished. Close-to-prägnant forms (i.e., “annäherend prägnant”; Goldmeier, 1982; Rausch, 1966) include those forms in the series that do not belong to the prägnant steps, but lie in their neighborhood. They embody the essence in a less good, “not (just) right” way (Metzger, 1941, p. 63). In the border area between the ranges of influence of two prägnant steps, one finds two other types of non-prägnant forms: meaningless (i.e., ‘nichtssagend’) structures, e.g., white noise on a tv screen, and ambiguous structures, which fluctuate between two Prägnanz ranges (Rausch, 1966, p. 907).

2.1.4 Good Gestalt

When comparing Gestalts varying on multiple properties in how “prägnant” they are, we discuss Prägnanz height (i.e., Prägnanzhöhe) or the goodness of a Gestalt. From the start, Prägnanz height has been very closely related to ideas on aesthetics. von Ehrenfels (1922, p. 50) regarded beauty as nothing else than Gestalt height. In its turn, Gestalt height is the product of the Gestalt’s level of complexity and order (von Ehrenfels, 1916). Rausch (1966, p. 926) indicated that if an organism can handle the complexity of a phenomenon, this phenomenon will be more prägnant than another phenomenon that is lower in order, complexity, or both.

Good Gestalt has a clear relation to the Prägnanz tendency as well. Metzger (1941) indicated that true artists will go beyond their models in the direction of Prägnanz, which means that they will come to a structure that more purely and compellingly specifies the essence of content of the artwork. To make the essence clearer, they can use simplification and/or complication strategies. Also in art, these tension reducing and tension promoting form changes can be concurrently present (Arnheim, 1975). In his late works, Piet Mondrian for example used rectangularity and primary colours, which served to simplify, but the irregular spacing was a complication, which served to make his work more dynamic (Arnheim, 1975, p. 281).

In my own view, some forms of aesthetic appreciation may be related to an increase in Prägnanz rather than to Prägnanz itself (Van Geert & Wagemans, 2018). In addition, also in the context of aesthetics inter- (and intra-) individual differences may play an important role in what will be the goodness level of a Gestalt.

2.2 Predictive coding and Prägnanz

Although my ideas on the relation between Prägnanz and predictive coding are still under development, I present my current way of thinking on their relationship.

Whereas predictive coding aims to clarify how (i.e., what are the underlying processes?), Gestalt theory and Prägnanz focus more on the experiential level and the why of perceptual organization. Their underlying concepts seem very similar, however.

As Koffka (1935) stated, we will tend towards the best organization possible under the prevailing conditions. These conditions include both internal and external conditions. In predictive processing, the available priors are part of the internal conditions influencing percept formation, whereas the likelihood relates to the visual input the individual receives. This combination of prior expectations and input leads to the computation of a posterior as well as a prediction error (at different processing levels, see Figure B.1). Once a prediction error emerges, the organism has to decide whether it will change its prior expectations to reduce the prediction error or treat the prediction error as uninformative and ignore it.

In the near future, I aim to elaborate more on the relation between predictive processing and Prägnanz, and give more concrete pointers on how the Prägnanz idea can add to the predictive processing paradigm and other current perspectives on visual perception. All projects presented in this mid-term report in some way relate to the general Prägnanz framework in Figure B.2: The specific combination of internal and external conditions, related to stimulus, person, and context, codetermine what will be perceived and how prägnant that percept will be. The Prägnanz level of a percept can in its turn have several behavioral effects, including effects on perceptual categorization, discrimination, and aesthetic appreciation.

Due to the worldwide coronavirus outbreak, both the workshop “Developing Models of the World” (16-20 March 2020, Leiden, The Netherlands) and the summer school “Complexity Methods for Behavioural Science: A Toolbox for Studying Change” (6-10 July 2020, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) to which I was accepted are postponed.↩︎