1 General introduction

As humans, our visual abilities are amongst the most important tools we possess to enable immediate interaction with the world around us. Without visual perception, many everyday activities like preparing breakfast, navigating the streets, and reading, become much more exhausting or even impossible.

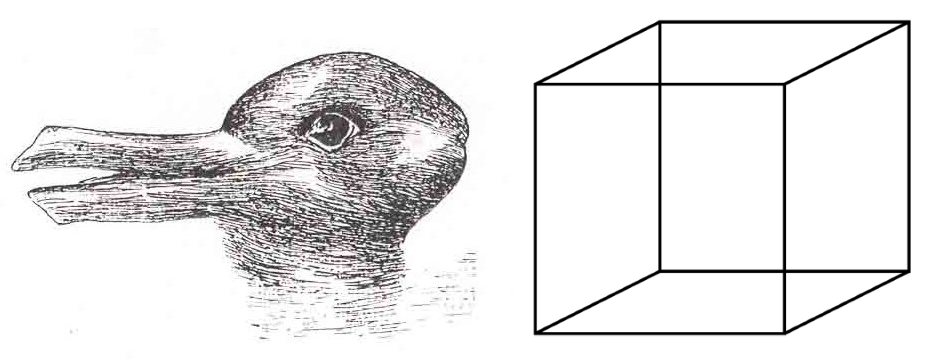

Although vision is sometimes presented as fully determined by the physical input it receives (i.e., light signals falling on the receptor cells in the retina), this is not the full story of how our perceptual experiences come about. An evident illustration is the existence of multistable figures like the duck-rabbit figure or the Necker cube (see Figure 1.1). Although the physical input stays exactly the same, each of these figures is perceived differently across individuals, contexts, and time. Visual perception is an active construction process, not only for obviously multistable figures. Even in so called clear-cut displays inter- and intra-individual differences exist based on, e.g., perceptual skills, viewing mode, expertise, vigilance level, and temporal or spatial context. Koffka (1935) already acknowledged that things look as they do, not because things are what they are (veridicality), nor because of the proximal stimuli (i.e., the physical stimulations of the sensory receptors) are what they are, but “because of the field organization to which the proximal stimulus distribution gives rise” (p. 98). In other words, to understand why and how we visually perceive the world in the way we do, we need to study the laws of psycho-physical1 organization (Koffka, 1935).

Koffka (1935) presented the law of Prägnanz as the main principle to guide this research on psycho-physical organization. The law of Prägnanz states that psycho-physical organization will always be as ‘good’ as the prevailing conditions allow: we will always organize the input in the best way possible given the prevailing circumstances. However, (a) what does it mean for an organization to be ‘good’ or ‘prägnant’, (b) how do we clarify the input to arrive at a better organization, and (c) what are the prevailing conditions to take into account? Notwithstanding the abundant reference to Prägnanz in many journal article introductions and discussion sections since its emergence, modern-day mentions of Prägnanz often lack these further clarifications. In addition, the original Gestalt psychological context in which Prägnanz originated got lost, and the interpretation of Prägnanz has changed together with the shifting theoretical context (i.e., increasing focus on information processing theories).

The overall aim of this dissertation is to arrive at a more fine-grained understanding of Prägnanz (i.e., “goodness” of organization) and its added value for current theories and research on human visual perception and aesthetic appreciation. Thoroughly understanding what Prägnanz and the law of Prägnanz mean and can mean for current perception science first of all requires a thorough investigation of the existing literature on the Prägnanz concept. This includes studying the original sources introducing and extending the concept as well as other sources clarifying later interpretations, proposed quantifications, and critiques of the Prägnanz concept. Given the lack of digitalization and translation for many of the original German sources concerning Prägnanz, gathering and digesting this literature was not a trivial task. From this literature review (cf. Chapter 2 as well as the introduction below), it will become clear that the law of Prägnanz was posited as a general overarching principle. The goal was to stimulate concrete further investigation into specific organizational principles falling under this law, as well as into the ways in which these principles interact under diverse circumstances, depending on the stimulus, person, and context in question.

Taking Prägnanz as a generative framework for further research is exactly what the other chapters of this dissertation exemplify. The studies do not directly test the overarching principle, but take it as a starting point to explore the principles governing psycho-physical organization in more concrete cases.

In what follows, I give a sneak preview of what is to come. First, I discuss the most important lessons learned from reviewing the existing Prägnanz literature. Then, a brief introduction to each part of the dissertation follows. Afterwards, I highlight how each part connects to the overall Prägnanz framework.

1.1 Main aspects regarding Prägnanz

As mentioned, the law of Prägnanz states that psychological organization will always be as ‘good’ as possible given the prevailing conditions. But what does this imply concretely? To make the Prägnanz law a useful statement, it needs to be specified further (a) what a ‘good’ psychological organization entails, (b) how the Prägnanz tendency can be realized, and (c) which conditions need to be taken into account (cf. also Chapter 2). Although the Gestalt school did provide answers to these questions, more recent references to Prägnanz often lack these clarifications.

1.1.1 What is a ‘good’ organization?

Prägnanz concerns the goodness or simplicity of an experienced overall organization. Importantly, Prägnanz thus is a property of percepts — not stimuli. Hence, what a ‘good’ organization entails, will depend not only on the incoming visual stimulation, but also on the perceiving organism and the context in which the input is encountered. Moreover, as Prägnanz focuses on the goodness of the experienced overall organization, it is neither to be equated with the simplicity of the elements part of the overall organization, nor with the simplicity of the process to form the overall organization.

To be experienced as ‘good’ or ‘prägnant’, a psychological organization needs to be different from a simple sum of its sensory elements: it has to be a Gestalt (Koffka, 1935; Smith, 1988; Wertheimer, 1922). A Gestalt is defined here as an experienced ensemble of elements that mutually support and determine one another (Ash, 1995; Köhler, 1920; Sundqvist, 2003). Therefore, to be experienced as a Gestalt, at least some form of unity or regularity should be experienced in the organization (Rausch, 1966). A Gestalt can be differentiated from a ‘complex’, in which the sensory elements are experienced as completely independent of each other — as a pure and-summation (Koffka, 1935; Smith, 1988).

The experienced unity or regularity can be due to purely figural or structural aspects, but can also be based on a match between structure and meaning (i.e., how purely and compellingly the structure represents an ‘essence’ or ‘way of being’; Metzger, 1941), or on how strongly the experienced organization interacts with already existing knowledge within the perceiver (i.e., how meaningful the perceiver experiences the organization to be). For example, the artist Constantin Brâncuși represented the concept of a bird by bringing it back to its essence: one feather in this case (cf. Figure 1.2). Furthermore, even on the figural level, an organization can be considered good on diverse grounds, related to both order (i.e., the structure and organization of elements2) and complexity (i.e., the quantity and variety of elements).

Rausch (1966) summarized these factors influencing the goodness of an experienced organization in seven Prägnanz aspects. The presence of at least some form of (1) lawfulness or regularity is posited as the first and only necessary Prägnanz aspect. In addition, the goodness of an organization can increase when the organization is perceived as (2) autonomous rather than derived, (3) complete rather than disrupted, (4) simple of structure rather than complicated of structure, (5) element rich rather than element poor, (6) expressive rather than expressionless, and (7) meaningful rather than meaningless. Prägnanz or goodness of organization is thus a multifaceted concept: an experienced organization can be ‘good’ or ‘better’ for many different reasons.

Psychological organizations that excel in their Prägnanz can influence our experience of new incoming information: they can serve as a reference to which the input is internally compared. In this context, the term Prägnanz steps [Prägnanzstufen] is used to refer to prägnant forms that serve as reference regions on a dimension (e.g., the right angle in the realm of all possible angles).

1.1.2 How do we clarify the input to arrive at a better organization?

The tendency towards Prägnanz of a Gestalt indicates a tendency present in every process of psychological organization to come to the best, most clear-cut (i.e., most prägnant) organization given the prevailing conditions (Arnheim, 1975; Koffka, 1935; Köhler, 1920; Metzger, 1941). But how do we clarify the incoming stimulation to arrive at a better organization? In all cases, the incoming stimulation is compared to a ‘reference’. This reference can be an internal representation of a good Gestalt (i.e., a Prägnanz step) or a reference present in the immediate spatial or temporal context. For example, when perceiving a chihuahua, the height of this chihuahua may be compared to the height of our internal representation of a prototypical dog. On the other hand, the height of the chihuahua may be compared to a locally present reference, for example, to the height of a fence present next to the dog, or to another even smaller chihuahua seen just before. Rather than a binary distinction between reference points and non-reference points, a gradual Prägnanz function applies to each variable dimension (e.g., height), with some regions showing higher Prägnanz than others. Furthermore, the course of this Prägnanz function per domain and dimension can differ between individuals and contexts. For example, the owner of a chihuahua may have different reference regions for dog height than the owner of a shepherd.

Gestalt psychology posited two main ways in which we can use this reference to clarify the incoming stimulation and come to a better Gestalt. On the one hand, we can remove or downsize unimportant details (i.e., simplification, leveling, assimilation, attraction) to make the incoming stimulation more similar to our reference (Arnheim, 1986; Koffka, 1935; Metzger, 1941). On the other hand, we can add, emphasize, or intensify characteristic features of the current stimulation (i.e., complication, sharpening, articulation, repulsion) to make the incoming stimulation stand out more clearly in comparison to the reference (Arnheim, 1986; Koffka, 1935; Metzger, 1941). Both of these tendencies can contribute to the emergence of a ‘better’, clearer, simpler Gestalt. Koffka (1935) referred to these tendencies as ‘minimum simplicity’ (i.e., the simplicity of uniformity) and ‘maximum simplicity’ (i.e., the simplicity of perfect articulation). Arnheim (1986) referred to them as ‘tension-reducing’ (i.e., decreasing the difference from the reference) and ‘tension-enhancing’ tendencies (i.e., increasing the difference from the reference and thereby making the currently experienced organization more unique). Koffka (1935) presented minimum and maximum simplicity as strict alternatives, and when viewed from a one-dimensional standpoint they certainly are: one either perceives the chihuahua’s height as more similar to the height of a prototypical dog than is actually the case (i.e., simplification), or one exaggerates the smallness of the chihuahua even more than in reality (i.e., complication). I agree with Arnheim (1986), however, that simplification and complication are concurrently present in every perceptual event. In any real-life situation, the incoming stimulation is inherently multidimensional. In our example, the chihuahua is not only evaluated on its height, but maybe also based on its color, cuteness, etc. Therefore, in any multidimensional situation, simplification and complication — although antagonistic in the one-dimensional case — can be complementary and work together to increase the goodness of the experienced organization (cf. also Arnheim, 1986; Hubbell, 1940; Köhler, 1951/1993).

As a sidenote: Whereas one could equate simplification with literally ‘removing’ features and complication with ‘adding’ features, this does not have to be the case. For example, a square missing one of its four sides may be simplified by adding a sideline, resulting in a complete square. On the other hand, also removing a part of an organization can complicate an organization, e.g., removing a sideline from a full square.

Reference points can thus serve a double function. On the one hand, a reference point can serve as a magnet: assimilation to the reference may occur, especially when the incoming stimulation is rather weak. This tendency makes perception more robust: perceived organizations will be closer together than the stimuli from which they originate. On the other hand, a reference point can serve as an anchor: they can increase sensitivity in their vicinity (i.e., increase the ability to notice small deviations from the reference). In that sense, reference points support both robustness and sensitivity in visual experience. Under weak stimulus conditions (i.e., under low visibility) or when a specific difference from the reference is deemed unimportant, attraction to the reference will dominate. Under clear stimulus conditions and when a specific difference is experienced as significant, reference points will increase discrimination sensitivity in those regions where deviations matter most (i.e., close to the reference). The stimulating effect of reference points on discrimination sensitivity also allows for the formation of new reference levels in between existing ones when this becomes behaviorally or functionally useful. Which of the features of the organization will be treated as characteristic and which as unimportant will depend on the individual and the context in which the organization is perceived. That is, to determine which features will be part of the experienced organization’s essence, it will matter in comparison to which reference the organization is perceived. Importantly, this dependence of the preferred tendency (i.e., simplification or complication) on the prevailing conditions does not make the Prägnanz tendency an empty statement, it does not imply that ‘anything is possible’. What it does imply is that individual and context need to be taken into the equation in further research on Prägnanz tendencies, to determine which tendency will occur for which feature dimension under which concrete conditions.

In addition to the distinction between simplification and complication tendencies, also primary and secondary Prägnanz tendencies can be distinguished (Hüppe, 1984). The primary Prägnanz tendency considers the relation between the incoming stimulation and the phenomenally experienced organization resulting from the stimulation. More specifically, the primary Prägnanz tendency leads to deviations from the incoming stimulation to the perceived organization that are not directly noticeable by the observer. In other words, every phenomenal experience already deviates from the stimulus in the direction of Prägnanz. The secondary Prägnanz tendency operates on the level of phenomenal experience. It concerns the tendency to evaluate a perceived organization based on its experienced closeness to a prägnant form (i.e., a point of comparison, not necessarily phenomenally present). This secondary Prägnanz tendency may sometimes reach awareness. Both Prägnanz tendencies cannot be seen as completely independent, however: To be able to make statements about secondary Prägnanz, an organized perceptual field (influenced by primary Prägnanz) is preassumed. Importantly, I do not think of these primary and secondary Prägnanz tendencies as successive processes. On the contrary, I believe that according to traditional Gestalt theory, there is not first an organization of the perceptual field and only then more high-level cognitive identification or classification, but rather one complex dynamic process of Gestalt formation (see also Kruse, 1986).

The Prägnanz tendency, i.e., the tendency towards the best psychological organization possible given the prevailing conditions, can thus not only lead to clearer percepts (i.e., primary Prägnanz tendency), but it can also play a role in how we — cognitively, emotionally, or aesthetically — evaluate (and communicate) our psychologically experienced organization (i.e., secondary Prägnanz tendency). In my dissertation, I focus on human visual perception and how it may influence several cognitive and aesthetic evaluations of those perceived organizations.

As perceptual processing of the incoming information is necessary to be able to aesthetically evaluate a percept, the close relation between perception and aesthetics cannot be neglected. von Ehrenfels (1922) equated beauty and Gestalt height, which he defined as the product of unity (of the whole) and multiplicity (of the parts; von Ehrenfels, 1916). Moreover, Koffka (1940) called perception artistic and both Metzger (1941) and Arnheim (1975) noticed the presence of simplification and complication tendencies in artistic practice. Although most authors agree that there is a close relationship between aesthetics and Gestalt, there are two differing views on the exact relation. On the one hand, as von Ehrenfels (1916, 1922) proposed, aesthetic appreciation may be based on the absolute goodness level of the experienced organization (i.e., Prägnanz height). On the other hand, aesthetic appreciation may arise together with a consciously experienced increase in Prägnanz (i.e., the strength of the experienced Prägnanz tendency), and this does not necessarily relate to the absolute Prägnanz height. This second view relates closely to some other existing accounts of aesthetic appreciation, including the predictive processing accounts of Van de Cruys & Wagemans (2011) and Chetverikov & Kristjánsson (2016) as well as the focus on pleasure by insights into Gestalt proposed by Muth and Carbon (Muth et al., 2013; Muth & Carbon, 2013, 2016). Both views may act complementarily as well, however, and future research can investigate the relation between aesthetics and Prägnanz in more detail.

Although this dissertation focuses on human visual perception and aesthetic appreciation, the tendency towards prägnant overall organizations is meant to be a very general tendency. The Prägnanz tendency was expected to be present in all forms of psychological organization (e.g., Koffka, 1935; Köhler, 1920; Metzger, 1936/2006), for all types of stimulation (i.e., simple or complex), and for all types of species. In this context, it is important to stress that the Prägnanz tendency, present in every psychological organizational process, will not always result in a ‘good’ Gestalt in the absolute sense (Arnheim, 1987; Koffka, 1935; Metzger, 1941). The tendency towards the most prägnant Gestalt should thus always be seen as relative to the prevailing conditions.

1.1.3 What are the prevailing conditions to take into account?

As psychological organization takes place in an organism, it is constrained by the conditions outlined by the organism. Hence, in determining the goodness of an organization, not only the stimulus constellation will play a role, but also how the stimulus interacts with an individual in a specific spatial and temporal context. When it concerns psycho-physical processes like human perceptual organization, there are both external and internal conditions to consider (Koffka, 1935). External conditions are created by the proximal stimuli, i.e., the excitations within the receptor organs to which the light rays coming from the physical object give rise. Under weak external conditions (e.g., because of brief exposure time, low contrast, small size), Prägnanz tendencies will get more room to play a role and can even lead to tangible dislocations and distortions compared to the external stimulation (Koffka, 1935). The factors mentioned under weak external conditions relate to low visibility. It is important, however, to explicitly distinguish this overall uncertainty from any uncertainty or ambiguity present in the features of the stimulus (e.g., uncertainty in directions present in a random dot kinematogram, ambiguity in orientations present in a multistable dot lattice). Internal conditions are related to the structure and/or state of the organism’s nervous system. Within the internal conditions, more permanent ones (related to the structure of the nervous system, influenced by both inheritance and previous experience) and more temporary ones (related to, e.g., vigilance, fatigue, needs, attitudes, interests, attentions; Koffka, 1935) can be distinguished.

1.1.4 The many faces of ‘Prägnanz’3

Based on the extensive Gestalt literature on the topic, I conclude that Prägnanz has many faces. For instance, Prägnanz has been used to refer to both (a) a tendency present in every organizational process and (b) the goodness level of an experienced organization resulting from this Prägnanz tendency. Moreover, the term ‘Prägnanz steps’ is used to refer to reference regions with high Prägnanz when a single perceptual dimension is varied. In addition, Prägnanz is also regularly referred to in the context of aesthetic appreciation and artistic practice.

Furthermore, also within each of these use contexts, the multifacetedness of Prägnanz prevails. As a property of an experienced organization, Metzger (1941) stressed how both figural order and the pure, compelling embodiment of an essence are essential to understand the full meaning of Prägnanz, and Rausch (1966) posited seven general factors contributing to Prägnanz. As a tendency in every organizational process, Prägnanz can show as an attractive and/or a repulsive tendency relative to an internal or a local reference. Furthermore, the Prägnanz tendency can be primary (i.e., an unconscious difference between stimulus and percept) or secondary (i.e., a sometimes conscious evaluation of the closeness of an experienced organization to a reference). Furthermore, the seven Prägnanz aspects posited by Rausch (1966) can also point to the existence of different Prägnanz tendencies.

Although some may view this multifacetedness of Prägnanz as problematic, and leave Prägnanz and Gestalt theory behind because of this experienced ‘vagueness’, it is important to clarify the original goal with which Prägnanz was posited. The Prägnanz principle was never meant as a magical one-fits-all solution, and should therefore not be seen solely as an outcome of concrete research results, but also as a device for making new discoveries (Wertheimer, 1924/1999). By using Gestalt theory and the Prägnanz principle as a generative framework for future research, and studying more specific principles of organization and their interaction in concrete cases (Rausch, 1966), we can come to a better understanding of the principles underlying psychological organization.

Hence, the multifacetedness of Prägnanz, and its dependence on input, person, and context, does not imply that ‘anything is possible’. Prägnanz provides a framework that highlights potential universality and diversity (i.e., constraints on generality) in psychological organization: different stimuli can lead to similar perceived organizations within an individual, while the same stimulation can be perceived differently depending on individual and context. The consideration of these interactions and dependencies does not render specific organizational principles following from the Prägnanz framework and under prespecified conditions untestable. And when it concerns Prägnanz as the overall framework, its validity should follow from observing these specific organizational principles under diverse circumstances. Only by organizing all these concrete observations in a coherent whole, we can come to the knowledge of a system (Koffka, 1935; cf. also Chapter 8). Hence, only because of its multifacetedness does Prägnanz provide a valuable generative framework for current cognitive science. In my dissertation, I attempt to bring this perspective on Prägnanz into practice. Each of the themes and studies introduced below relates to this overall framework, and in this introduction I aim to make the connection clear.

1.2 Preview on empirical work

1.2.1 Robustness and sensitivity

The part on robustness and sensitivity deals with how we can use internal representations of good Gestalts (i.e., Prägnanz steps) as a reference for comparison to arrive at a clearer percept. More specifically, these internal representations can support perceptual stability — related to robust categorization — while they can also support sensitivity to perceptual change — related to discrimination. In the empirical study reported in Chapter 3, we were interested in investigating the category boundary effect in perceptual discrimination and similarity judgments. The category boundary effect entails that even when keeping the physical difference between stimuli the same, differences between stimuli belonging to the same category are perceived as smaller than differences between stimuli belonging to different categories. Typically, this is tested and interpreted as an effect of the category boundary: performance on trials with between-category stimulus pairs is compared to performance on trials with within-category stimulus pairs (while equating the size of the difference between the stimuli in both types of pairs). However, we propose that the existence of reference points (i.e., exemplars that serve as a point of comparison) can explain the occurrence of the category boundary effect.

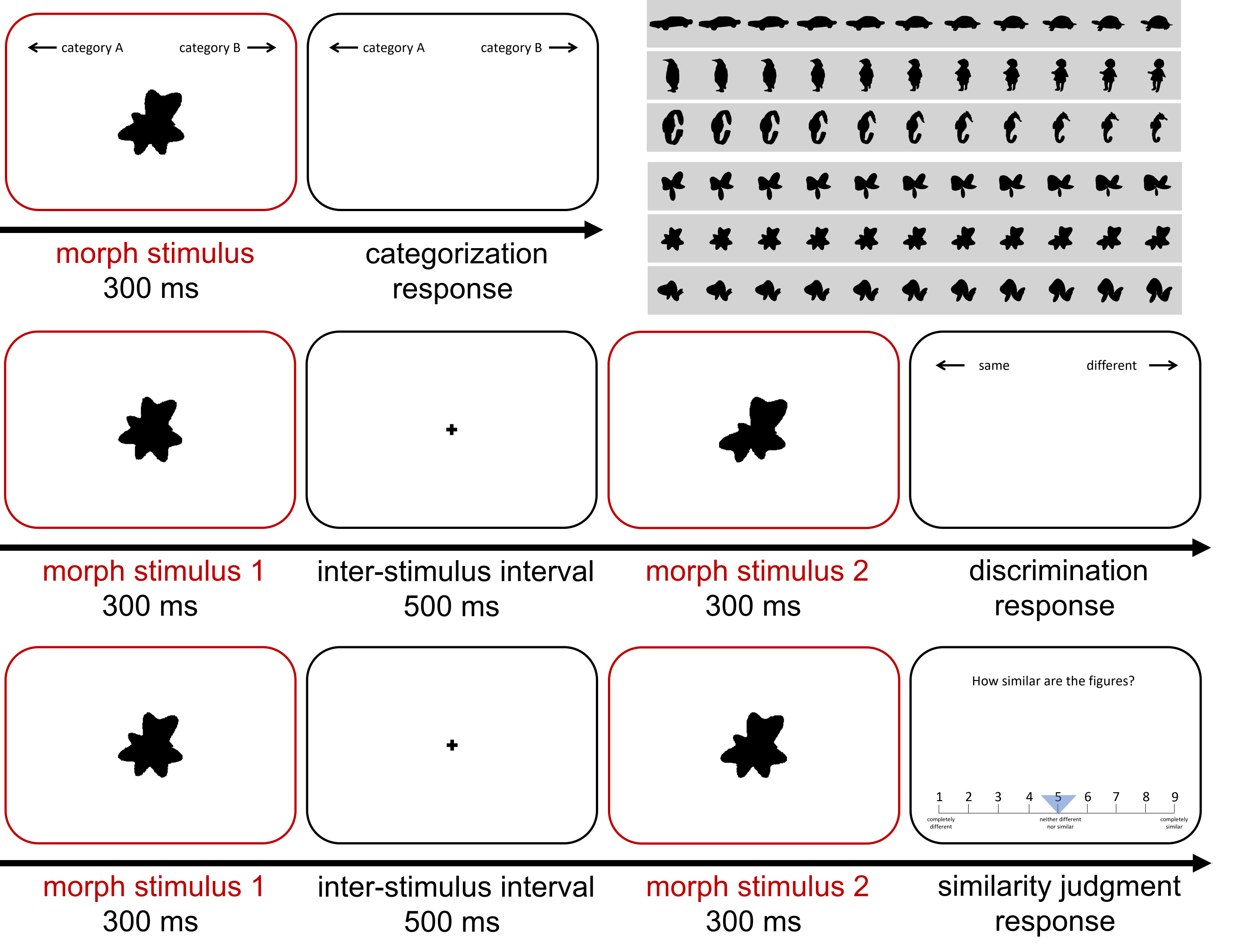

We asked participants to perform categorization, discrimination, and similarity judgments for different sets of morph figures (cf. Figure 1.3). Some of these sets morphed between clearly recognizable shapes (e.g., a car and a tortoise), other sets morphed between non-recognizable abstract shapes. Although we replicated the overall category boundary effect for both discrimination and similarity, we show that what mattered for actually predicting discrimination performance and similarity judgments was not the type of stimulus pair (i.e., within-category or between-category), but (a) the strength of the reference points and (b) the difference from the reference points for each of the individual stimuli in the pair.

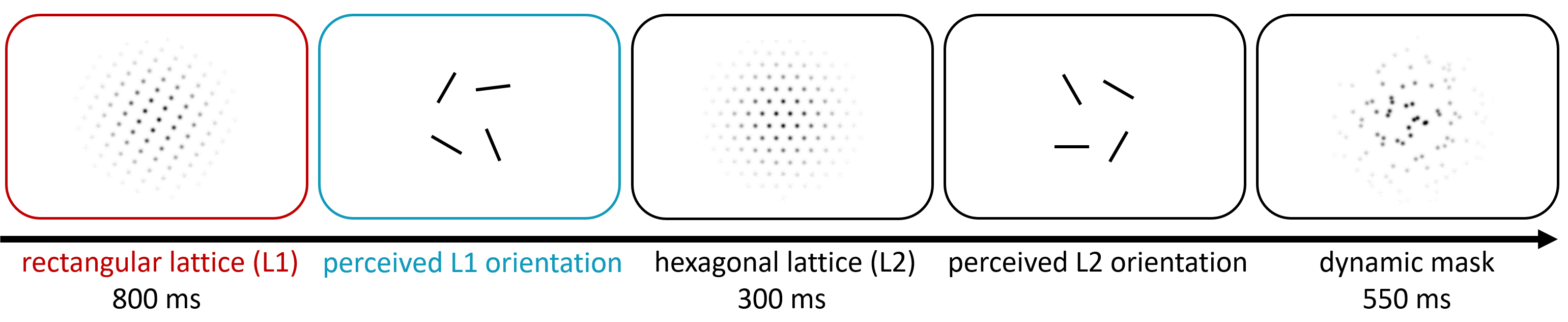

1.2.2 Hysteresis and adaptation

The part on hysteresis and adaptation deals with how we can use the immediate temporal context — including both perceptual history and stimulus history — to clarify our perception of the incoming stimulation. More specifically, earlier research has found an attractive effect of the previous percept on the current percept (i.e., hysteresis: we more often perceive what we have perceived before) and a repulsive effect of the previous stimulus evidence on the current percept (i.e., adaptation: we less often perceive the organization for which there was most evidence in the previous stimulus; e.g., Gepshtein & Kubovy, 2005; Schwiedrzik et al., 2014). In these earlier studies, these effects were often studied at the group level, averaged across participants. In Chapter 4, we investigate potential individual differences in the size and direction of these immediate temporal context effects, in a multistable dot lattice paradigm (cf. Figure 1.4). Furthermore, we test the temporal stability of these individual differences. Although almost everyone showed an attractive effect of the previous percept and a repulsive effect of the previous stimulus evidence, not every single participant did. Furthermore, participants differed consistently in the extent to which they used previous input and experience in combination with current input to shape their perception, and these individual differences showed stable across one to two weeks’ time. In Chapter 5, we develop an efficient Bayesian observer model and discuss how it can explain the co-occurrence of attractive and repulsive temporal context effects in this multistable dot lattice paradigm. An efficient Bayesian observer model differs from traditional Bayesian inference in that it assumes variable encoding precision of feature values in line with their frequency of occurrence, and as a consequence can predict biases away from the peak of the prior. Efficient encoding and likelihood repulsion on the stimulus level could explain the repulsive effect of the previous stimulus evidence, while perceptual prior attraction could explain the attractive effect of the previous percept.

1.2.3 Simplification and complication

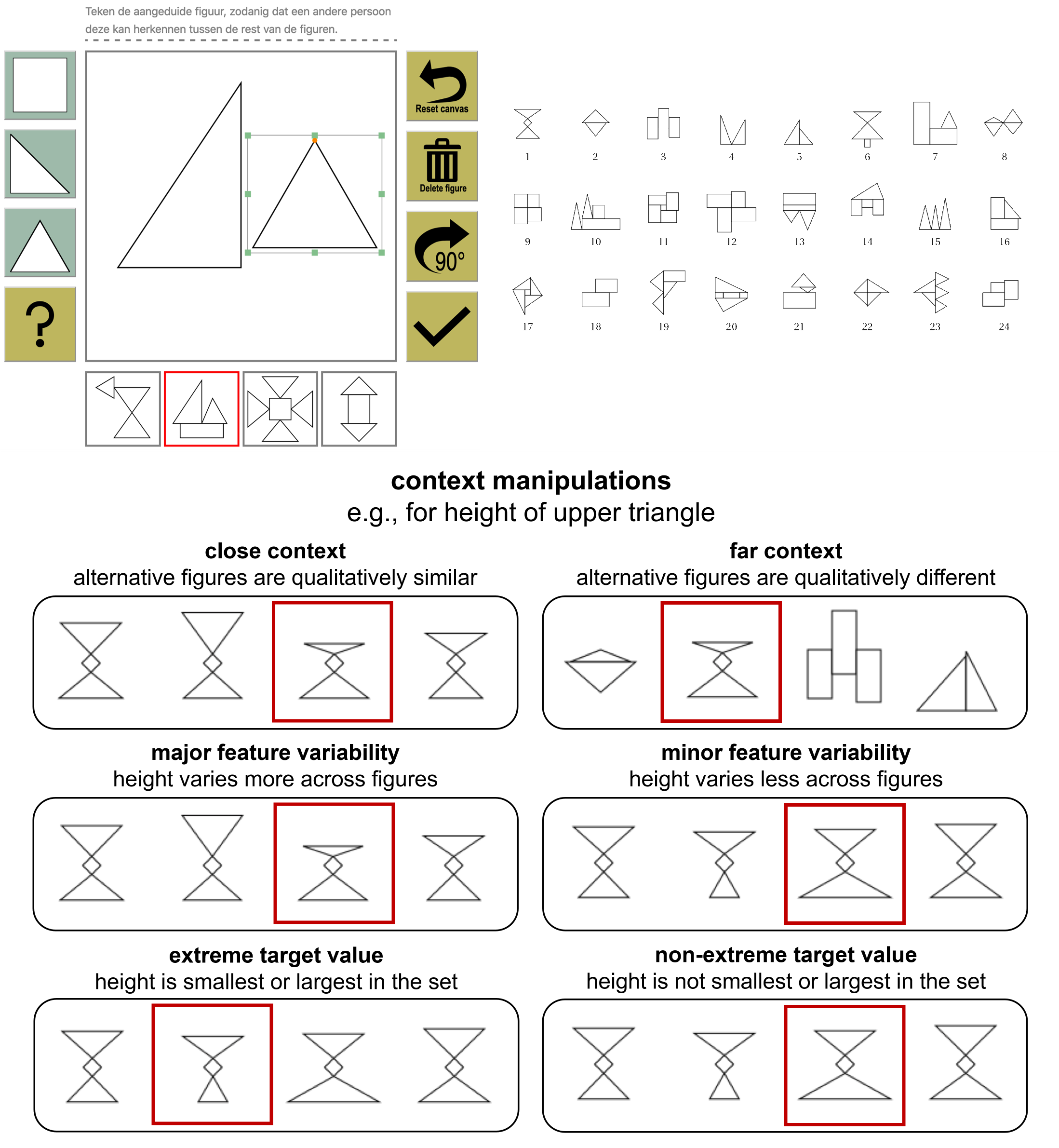

The part on simplification and complication deals with how we can use the immediate spatial context to clarify our perception of the incoming stimulation. Gestalt theory posited two ways to make an organization more clear: either by removing unimportant details and making the experienced organization more similar to a reference (i.e., simplification), or by emphasizing characteristic features and making the organization stand out more from the reference (i.e., complication; Arnheim, 1986; Koffka, 1935). But when will a feature be simplified and when will it be complicated? In Chapter 6, we investigated whether the importance of a feature for discrimination among alternatives influences which organizational tendency will occur. Participants were presented with four figures composed of simple geometrical shapes simultaneously. One of these figures was indicated as the target figure, and participants were asked to reconstruct this target figure in such a way that another participant would be able to recognize it among the alternatives. Importance of a feature for discrimination was operationalized in three different ways (cf. Figure 1.5). Firstly, the four figures differed either qualitatively or only quantitatively (i.e., far or close context). Secondly, in close contexts, figures varied on two feature dimensions, and for one feature the range of variability across the alternatives was larger than for the other feature. Thirdly, in the case of a smaller variability range, the target figure was either at the extreme of the range or had an in-between value. The results indicated that each of these manipulations influenced the probability with which a feature was simplified or complicated. More specifically, complication occurred more often for the feature with an extreme value, for the feature exhibiting more variability, and for the features of figures presented in the close context, than for the feature with a non-extreme value, exhibiting less variability, or in the far context (i.e., more complication for the examples in the left columns than in the right columns of Figure 1.5). In other words, the immediate spatial context in which a percept is formed could influence which features were experienced as characteristic or rather unnecessary.

1.2.4 Order and complexity

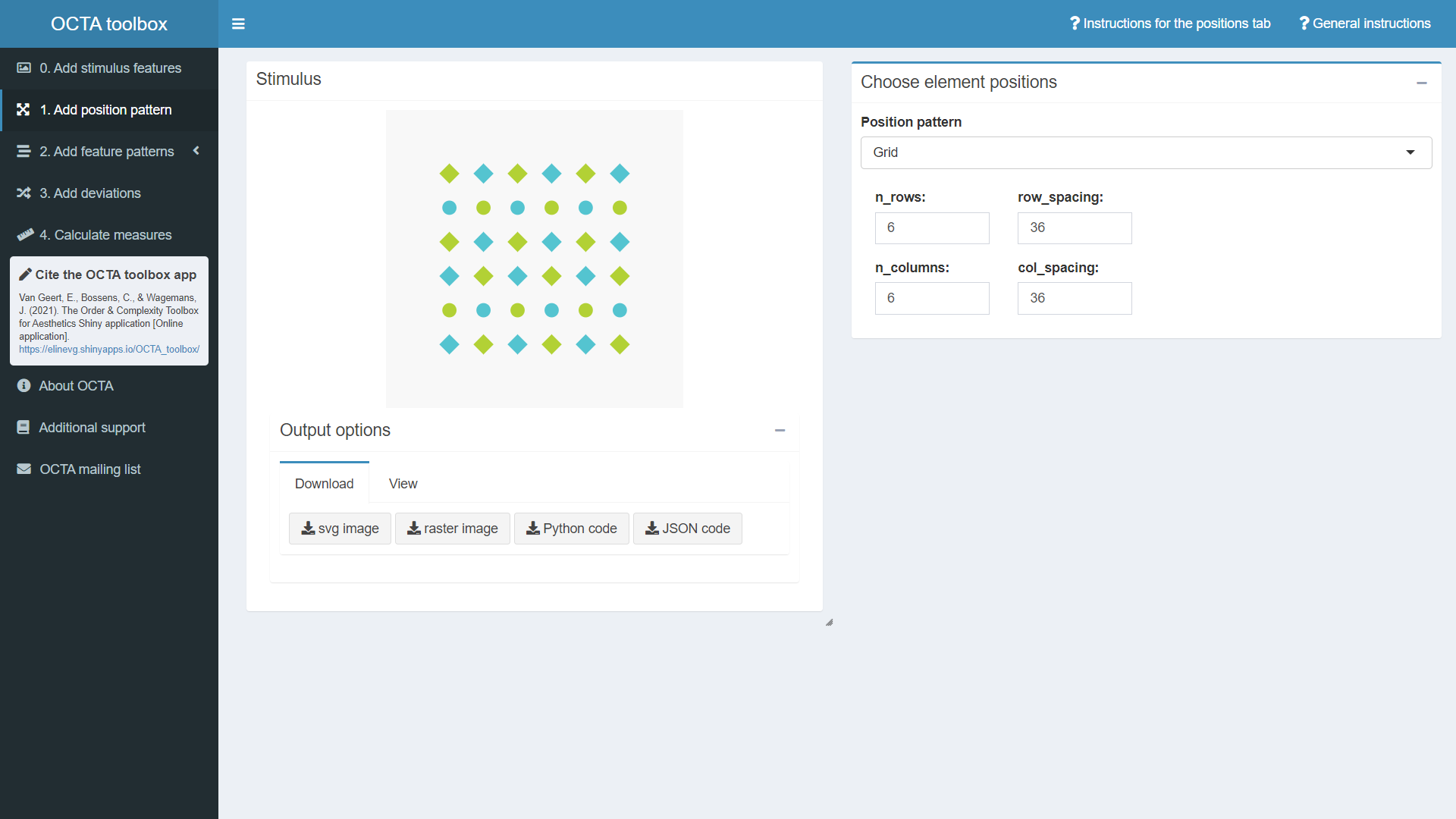

The part on order and complexity deals with how the factors that contribute to increased clarity (i.e., Prägnanz) of our percepts can also contribute to aesthetic appreciation. As mentioned above under “What is a ‘good’ organization?”, both order and complexity can increase the clarity of an experienced organization. Earlier research has often found relations between order, complexity, and aesthetic appreciation (for an overview, see Van Geert & Wagemans, 2020), but the exact type and direction of this relation has remained unclear. Many studies have investigated the influences of order and complexity separately, have focused on specific types of order, ignored the multidimensionality of order and complexity, and/or did not manipulate order and complexity in a standardized manner. In Chapter 7, we present the Order & Complexity Toolbox for Aesthetics (OCTA), a Python toolbox that provides a free and easy way to create reproducible multi-element displays including both order and complexity manipulations. Furthermore, OCTA is also available as a point-and-click Shiny application (cf. Figure 1.6), which allows researchers without any programming experience to also use the toolbox and construct reproducible stimuli for their research.

1.3 How does it all connect?

1.3.1 Robustness and sensitivity

The part on robustness and sensitivity focuses on how internal representations of good Gestalts (i.e., Prägnanz steps) are used as reference points to clarify the visual input. On the one hand, prägnant Gestalts can act as anchors, increasing sensitivity to change and discrimination performance around them. On the other hand, prägnant Gestalts can act as robust magnets, decreasing perceptual distance and worsening discrimination (Köhler, 1920; Stadler et al., 1979; Wertheimer, 1923). Relatedly, it is more difficult to transform prägnant figures into non-prägnant ones than the other way around (Goldmeier, 1937, 1982): also in that sense, prägnant Gestalts are more robust. As Wertheimer (1923) described it, shapes close to a prägnant step appear as [perceptually] different from but [categorically] related to the prägnant Gestalt: “as a somewhat ‘poorer’ version of it” (p. 318). In other words, although shapes close to the prägnant form can be perceptually discriminated from it, they are still categorized in relation to this prägnant form: the prägnant form serves as a reference point.

This double role of internal reference points in the Gestalt literature is congruent with the conclusion drawn by Quinn (2000), who discussed task context as a moderating factor for the role of perceptual reference points on discrimination sensitivity. On the one hand, increased sensitivity around reference points (above threshold) is present in tasks involving direct perceptual comparisons with plenty of perceptual evidence present and minimal memory demands. On the other hand, decreased sensitivity around reference points occurs for tasks in which a currently available stimulus was compared to stimuli stored in memory (i.e., for which there was limited perceptual input). Put differently, repulsive effects leading to increased sensitivity around reference points may be more related to ‘low-level’ perceptual processing, while attractive effects that decrease sensitivity and increase robustness may arise from ‘higher-level’ perceptual or cognitive processing (Quinn, 2000).

In Chapter 3, we propose that the existence of internal reference points (i.e., Prägnanz steps that serve as a point of comparison) and an attractive tendency towards these Prägnanz steps can explain the occurrence of the category boundary effect. Furthermore, we explain how the attractive tendency towards Prägnanz steps can also explain directional asymmetries in within-category pairs, i.e., worse discrimination when comparing a stimulus further away from the reference point to a stimulus closer to the reference point than the other way around.

In addition to the expected influence of Prägnanz steps on discrimination and similarity, we also expected an effect on categorization. As Prägnanz steps have been associated with more robust categorization — less prägnant Gestalts change their category membership more easily (Wertheimer, 1923) — we expected increasing categorization performance based the closer the stimulus was to an internal reference point.

The chapter thus focuses on investigating the relevance of internal reference points (i.e., Prägnanz steps) and the perceptual distance of the current stimulus from those internal reference points as determining factors for what the best possible perceptual and cognitive organization will be. Given that participants provide judgments that go further than only reporting their percept, both primary and secondary Prägnanz may be involved.

1.3.2 Hysteresis and adaptation

How do participants clarify the input when no clear internal reference points are present? In the section above, on possible Prägnanz tendencies, I discussed that sometimes, for example when no internal reference is available, a local reference may be used. This local reference is present in the immediate temporal or spatial context of the stimulus. In this part on hysteresis and adaptation, I focus on how immediate temporal context can be used as a (local) reference to clarify the visual input.

In the dot lattice study reported in Chapter 4, the current visual input was always ambiguous, and was also presented for only a short duration (i.e., weak stimulus conditions). The clarity of the previous stimulus varied across trials, however, and this stimulus was presented for a longer duration. Using an existing multistable dot lattice paradigm (Gepshtein & Kubovy, 2005; Schwiedrzik et al., 2014), we investigated individual differences in hysteresis and adaptation. The main questions of this study included whether (a) individual differences exist in the size of these temporal context effects, and if so, (b) whether everyone shows these effects in the expected direction, and (c) whether these individual differences are stable across one to two weeks’ time. In addition to these main interests, we investigated much more, all of which will be discussed in Chapter 4. Of particular interest to this general introduction may be that we also investigated the relation between the strength of long-term absolute orientation biases (i.e., strength of Prägnanz steps for orientation) and that of the attractive and repulsive short-term temporal context effects. Also, a control task was included to investigate whether the attractive temporal context effect was based on the previous percept and/or on the previous response/decision. We conducted this study as a Registered Report, which means that we first specified our methods and analysis plan and got in-principle-acceptance from the journal before we actually collected and analyzed the data.

Chapter 5 describes a model that can predict co-occurring attractive and repulsive temporal context effects using efficient encoding and Bayesian decoding. Moreover, the model gives an idea about how the attractive effect of the previous percept and the repulsive effect of the previous stimulus evidence may arise. Efficient Bayesian observer models (Mao & Stocker, 2022; Ni & Stocker, 2023; Wei & Stocker, 2015; Wei & Stocker, 2017) assume variable encoding precision of feature values in line with their (long- and/or short-term) frequency of occurrence: those feature values that occur more frequently are more accurately represented. In addition, frequency of occurrence also influences prior expectations for a feature value to occur. For example, cardinal orientations are more common than oblique ones, and therefore humans expect more cardinal orientations and represent them more accurately compared to oblique ones.

In contrast to other Bayesian observer models, efficient ones (a) can predict perceptual biases away from the peak of the prior (Wei & Stocker, 2015) and (b) take the dissimilarity between stimulus space and sensory space into account, leading to differential predictions for the influence of internal sensory noise (i.e., reduced visual strength as in Huang, 2015; Huang, 2022; e.g., less visible orientation because of brief presentation duration) and external stimulus noise (i.e., reduced featural strength as in Huang, 2015; Huang, 2022; e.g., high variance in the orientations present in the stimulus).

Several aspects of efficient Bayesian observer models relate closely to the Prägnanz framework discussed above. Firstly, efficient encoding puts a limit on the organism’s capacity to process the incoming stimulation. This assumption of a capacity limit can be categorized as part of the internal conditions discussed by Koffka (1935), and was referred to by Metzger (1941) as ‘comprehension capacity’ [Fassungsvermögen], influencing whether an organization would be experienced as unclear and chaotic or as rich and including multiple regularities. Furthermore, Koenderink et al. (2018) described this capacity limit as a ‘structural complexity bottleneck’. When the structural complexity of a stimulus exceeds the level of structural complexity that the organism can process, the stimulus will no longer be recognized as a “picture”, but rather as “featureless” or “just noise” (Koenderink et al., 2018). This capacity limit may be subject to contextual and individual differences, and thereby influence which Prägnanz tendencies will occur.

Secondly, the distinction between internal sensory noise and external stimulus noise may remind you of the distinction I made when relating Koffka’s (1935) weak external conditions to low visibility but not uncertainty present in the features of the stimulus. Koffka’s weak external conditions (i.e., low visibility) thus relate to the idea of high internal sensory noise in the efficient Bayesian observer model.

1.3.3 Simplification and complication

In this theme, I focus on how the Prägnanz tendency can play out by concurrent simplification, i.e., removing or weakening distracting, unnecessary details, and complication, i.e., intensifying characteristic features of the visual input (Arnheim, 1986). Which features are characteristic or rather unnecessary, however, and as a consequence, which features will more often be sharpened or leveled, respectively?

In Chapter 6, we research how the immediate spatial context can play a role in which features of the visual input are simplified or complicated to arrive at the best possible psychological organization given the conditions. We expected that in line with one of Metzger’s (1941) definitions of prägnant Gestalts (i.e., good Gestalts as those structures that most purely and compellingly represent an essence), the essence of a Gestalt may be context-dependent, and this could influence whether simplification or complication of a feature leads to the best organization in the specific context. More specifically, we hypothesized that the importance of a feature for discrimination within a specific (task) context would influence which organizational tendency would occur.

In the previous themes, the studies focused on situations in which the current stimulus was shown very briefly. In other words, the ‘external conditions’ were rather weak (Koffka, 1935). In this study, external conditions were rather strong: the stimulus and the surrounding context were shown for an unlimited amount of time. Furthermore, participants were instructed to draw a target figure in such a way that the another participant would be able to recognize it among the alternatives. The study may thus have targeted a rather conscious deviation from the target figure, to enhance its communicative value — and thus also its Prägnanz — despite the strong stimulus factors. These — potentially explicit — simplification and complication tendencies may be seen as rather similar to some of the conscious Prägnanz tendencies in artistic practice. Especially cartoon artists directly apply these tendencies: they exaggerate characteristic features (i.e., complication) as well as cleanse the stimulus from other, distracting details (i.e., simplification). This also relates to Hüppe’s (1984) description of the secondary Prägnanz tendency as a (potentially conscious) evaluation of the closeness of an experienced organization to a reference. As indicated, however, even in situations in which conscious deviations may be at play, primary Prägnanz tendencies can have an (unconscious) underlying influence too.

1.3.4 Order and complexity

The goodness of an experienced overall organization may increase with increasing order — think of the order-related, tension-reducing aspects listed by Rausch (1966), i.e., lawfulness, autonomy, integrity, and simplicity of structure — but can also increase with increasing intricacy or complexity — think of Rausch’s (1966) Prägnanz aspects of element richness, expressiveness, meaningfulness. Order and complexity are not only important contributors to a better, more prägnant organization, they have also often been related to our experience of aesthetic appreciation (Van Geert & Wagemans, 2020). Furthermore, order- and complexity-stimulating Prägnanz tendencies are as present in artistic practice as they are in perceptual organization. Metzger (1941) for example indicated that true artists will go beyond their models in the direction of Prägnanz. To do so, they can both intensify characteristic features (i.e., complication) or weaken unimportant details (i.e., simplification). But how do Prägnanz and aesthetic appreciation relate precisely?

This part on order and complexity discusses two potential perspectives on the relation between good psychological organization and aesthetic appreciation. On the one hand, von Ehrenfels (1922) called beauty nothing else than Gestalt height, which he earlier defined as the product of unity (of the whole) and multiplicity (of the parts; von Ehrenfels, 1916). This view focuses on the importance of the absolute Prägnanz level of a perceived organization for its aesthetic appreciation.

On the other hand, aesthetic appreciation could also be connected to the relative increase in Prägnanz that the perceiver experiences (i.e., the strength of the experienced Prägnanz tendency). This second view makes experiencing at least some lawfulness or regularity a requirement for both Prägnanz and aesthetic appreciation: some level of order always needs to be presented for an organization to be ‘good’ and to be appreciated. For complexity, however, the relation with Prägnanz and appreciation would be slightly different. If it is mainly the relative increase in Prägnanz that matters for aesthetic appreciation, complexity can play a larger role in aesthetics than in perceptual organization. Complexity-related factors (i.e., element richness, expressiveness, or meaningfulness) can increase the Prägnanz level of a psychological organization if the complexity stays within the capacity limits of the organism and does not diminish perceived order. In aesthetic appreciation, however, more perceived complexity means more room for increases in Prägnanz. A perceiver’s expectation to be able to handle the complexity (the individual’s perceived capacity limit) will still put a cap on the maximum level of complexity that can be appreciated. However, given that in aesthetics vagueness has not the same negative life-related consequences as in perceptual organization, in appreciation it is less crucial that the final experienced organization is maximally ordered. If only the potential to increase Prägnanz matters (and less the absolute Prägnanz level), and the perceiving organism has a relatively high capacity limit, complexity may play a bigger role in aesthetic appreciation than in perception. As indicated above, this second view relates closely to the predictive processing accounts of, for example, Van de Cruys & Wagemans (2011) and Chetverikov & Kristjánsson (2016) as well as the focus on pleasure by insights into Gestalt proposed by Muth and Carbon (Muth et al., 2013; Muth & Carbon, 2013, 2016).

Both views — appreciation as Prägnanz height and appreciation as experienced strength of the Prägnanz tendency — may act in complementary ways as well, however. This combination of views is in line with the pleasure-interest model of aesthetic liking (PIA model) proposed by Graf and Landwehr (2015, 2017). The PIA model suggests two separate pathways towards aesthetic liking: one resulting from immediate automatic processing of the visual input (resulting in the experience of pleasure; related to processing fluency), and a second one resulting from perceiver-driven controlled processing (resulting in the experience of interest). Translated to the order, complexity, and Prägnanz terminology (cf. also Van Geert & Wagemans, 2020), we suggest that interest (often for rather complex, element rich stimuli) only occurs on the condition that the perceiver is able to psychologically organize this complexity and experience enough order. In contrast, pleasure may result immediately (for rather simple, meager stimuli), as less Prägnanz tendencies are necessary to organize the input.

In our view, a minimum level of unity or order may be a prerequisite for aesthetic appreciation as it is for Prägnanz, but aesthetic appreciation is expected to arise together with a conscious increase in Prägnanz, and therefore also complexity may play an important role. Given that capacity limits may depend on individual and context, strong individual differences could be expected when it comes to the appreciation of complexity. Furthermore, in case both Prägnanz height and the strength of the experienced Prägnanz tendency matter for aesthetic appreciation (in line with the PIA model), the importance of both relations may differ between individuals and contexts.

In an empirical study using images of neatly organized compositions (Van Geert & Wagemans, 2021), which was part of my master’s thesis, I found that soothingness and fascination differ in their relations with complexity, but both relate positively to order and aesthetic appreciation. Furthermore, individual participants’ correlations of perceived soothingness and fascination with perceived complexity were much more variable than the correlations with perceived order. In a follow-up on this study, we compared native Chinese-speaking and native Dutch-speaking participants, and found the positive relation between appreciation and order to be cross-culturally consistent, but the relation between appreciation and complexity showed to be cross-culturally diverse (Van Geert et al., 2021).

In these above mentioned studies I conducted on the relation between order, complexity, and appreciation, stimulus materials were collected from the internet, and consequently were not parametrically controlled. Other existing research mainly focused on the separate influence of order and complexity on aesthetic appreciation, focused on rather specific types of order (i.e., balance or symmetry), and/or ignored the multidimensionality of order and complexity. I believe that progress has also been hindered by the lack of an easy way to create reproducible and expandible stimulus sets, including both order and complexity manipulations on multiple stimulus dimensions (e.g., color, shape, size, orientation).

Chapter 7 presents the Order & Complexity Toolbox for Aesthetics, a Python toolbox and online point-and-click application we created to enhance the reproducibility of stimuli used in research on the connection between order, complexity, and appreciation in the visual modality. This chapter focuses on how Prägnanz, and more specifically order and complexity-related aspects of Prägnanz, can play a role beyond perceptual organization, in forming aesthetic evaluations of visual stimuli.

1.3.5 General discussion

To perceptually clarify the incoming stimulation, both attractive and repulsive tendencies can concurrently be at play. While the attractive tendencies will make the perceived organization more similar to the reference, the repulsive tendencies will increase the perceived difference between the currently experienced organization and the reference. The reference can be based on an internal representation of a good Gestalt, the immediate temporal context, and/or the immediate spatial context surrounding the incoming stimulation. These attractive tension-reducing and repulsive tension-increasing tendencies — robustness and sensitivity (cf. Chapter 3), hysteresis and adaptation (cf. Chapters 4 and Chapter 5), simplification and complication (cf. Chapter 6), and order and complexity (cf. Chapter 7) — are antagonistic to some extent, but also work together (i.e., complement each other) to arrive at the best possible psychological organization given the prevailing conditions (i.e., the Prägnanz principle), to optimize a balance between what we already know and the new input we receive. Importantly, the effects of Prägnanz are not limited to perceptual organization, but have consequences in many other psychological processes, including aesthetic appreciation. For a longer overview of the general conclusions that can be drawn from this dissertation, as well as an outlook to future directions, I refer to the General discussion (cf. Chapter 8).

I call this ‘psycho-physical’ organization because the organization is influenced both by physical stimulation of the sensory receptors (i.e., the proximal stimuli) and psychological factors depending on the perceiving organism in question. This should not be confused with Fechner’s notion of psychophysics, which concerns the quantitative mapping of physical stimuli onto psychological entities (e.g., between stimulus intensity and sensation strength).↩︎

Although I refer to ‘elements’ here, I mean this in a broader sense than only the sensory elements part of the organization. The organization can, for example, be associated with multiple congruent meanings (cf. Chapter 2), which can also contribute to the order and complexity in the organization.↩︎

The title of this section was inspired by Arnheim’s (1986) article “The two faces of Gestalt psychology”.↩︎